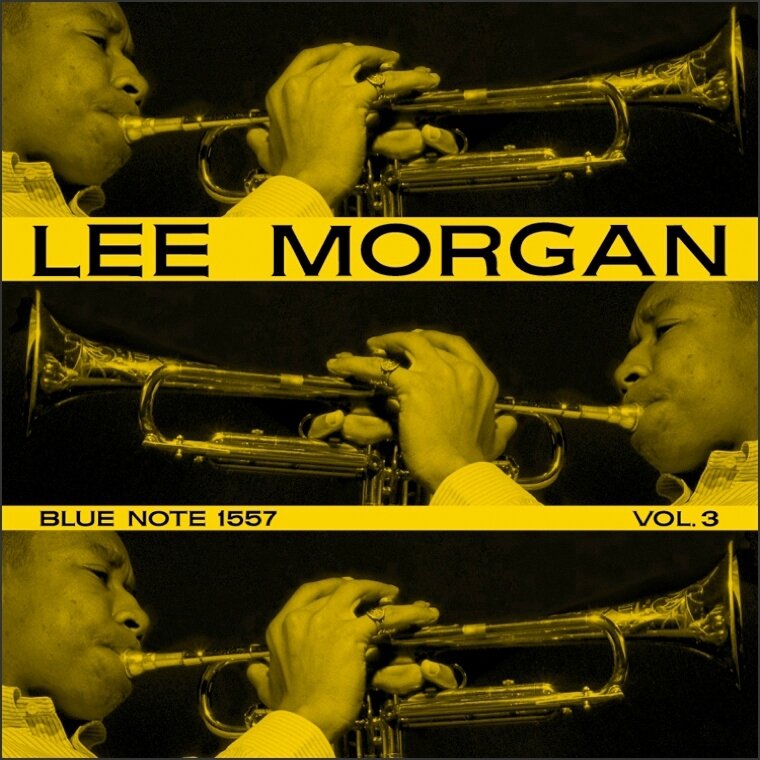

Personnel:

Lee Morgan (trumpet)

Joe Henderson (tenor sax)

Barry Harris (piano)

Bob Cranshaw (bass)

Billy Higgins (drums)

Recorded on December 21st, 1963

Availability: CD, MP3 download, iTunes

Tracks:

The Sidewinder; Totem Pole; Gary's Notebook; Boy, What a Night; Hocus Pocus

Review:

Simply one of the best jazz albums every released. There is a balance and economy about the five songs (all Lee Morgan compositions) and their performance that is seldom bettered. So, for example, although the opening track "The Sidewinder" runs for nearly 11 pulsating minutes, there is only just time for each of the four principals to solo once and for the whole package to be sandwiched between the opening and closing themes. Everything feels essential, necessary; one note extra or one note less in the whole piece would somehow have destroyed the balance achieved. The same could be said of "Gary's Notebook", a piece also notable for its perfect development of the tension and release aspect of hard bop as the band juxtapose between constraining and liberating time signatures. All the tracks are of the same high quality. The whole starts to sound like more than the sum of the parts the more times you listen to it.

Most reviewers concentrate on the commercial success of the title track. Back in 1964 it was unusual indeed for a jazz track to enter the Billboard top 100. It was also unusual for a new jazz track to be taken up by the advertising agencies. Both happpened to "The Sidewinder". ("The Sidewinder" formed the backing to Chrysler ads during the World Series). The only other Blue Note track with anything like similar success was Herbie Hancock's "Watermelon Man". The downside was that producer Alfred Lion, struggling to make a small indpendent jazz lable pay, apparently insisted on trying to repeat the success of these two songs repeatedly in the years to come. And that repeat success proved to be illusive.

In Lee Morgan's case, the attempt to produce another 'Sidewinder" had two limiting consequences: many of his best albums of the mid sixties were shelved before release since they did not have obvious "hit" potential and most of his albums that did make it to a release date had to start off with an opening track that was an attempt to emulate "The Sidewinder". This quickly became a formula that should have worked but did not. Somehow with the spontenaiety taken away, the balance and economy and the style that had been so overwhelmingly to the fore just melted away. It is a major surprise, however, in looking back on Alfred Lion's attempts to produce anothger "Sidewinder" that he never once assembled again the same five musicains that had come together to deliver the magic in the first place. However, the good news is that once the "Sidewinder clone issue" was taken care of, the creative freedom afforded by Blue Note was restored and a great deal of Lee Morgan's music (now made available again as remasterd CDs or as iTunes downloads) is recognised for its great value.

The performance of these five musicians in addition to Lee Morgan's inspired writing is what makes the album so great. It was one of the great difficulties of the time that outside of a very small number of key performers (Miles Davis, Art Blakey, Horace Silver amongst them) most jazz performers could not afford the luxury of keeping together a band that could go on developing. Too much of what had to be accomplished had to be done on severely limited resources. Making a living was about the next date with a different set of musicians, wherever that might be. So, what would have happened if this band could have stuck together?

This has much to do with the obscurity into which Joe Henderson's career had sunk before his rediscvovery in the 1990s. Without the centre of a continuing well known band set up, there was not a focus for his outstanding talents to be recognised. Compare the development of Wayne Shorter and Herbie Hancock from within the "shelter" of the Miles Davis group at this time. (Joe almost joined MIles ahead of Wayne in the mid sixites but somehow circumstances got in the way).

One day's rehearsal. It may not sound like much but that was what Blue Note offered for the first time and it went some way to remedying the problems of establishing rapport with a new group of musicians at each recording. In these days of pop groups spending over a year and a million dollars in the studio before an album release it is amazing what these jazzers achieved.

Lee Morgan's playing is mercurial as ever. As composer, he is careful not to overdominate. There is space, time and room for the other players. Barry Harris' piano playing is subtle and unshowy, something that you almost take for granted on a first hearing. But it is its sparseness and deep rhythmical sense and the way that it couples with Billy Higgins' drumming that is the key.

When John Scofield formed his "dream jazz group" for a one off album performance ("Works for Me") in January 2000, he made it clear why he so much wanted Billy Higgins in the band: "His beat and creativity make the music come alive". And this is precisely true of "The Sidewinder". Indeed, you only have to look at the number of great jazz albums that have been informed by Billy Higgins' beat and creativity to understand what an important player he has been in this music's success over a forty year period.

And what of Joe Henderson? Joe is not just a great saxaphone player heard here at his finest. He is a great empathiser. His is a modest and deeply democratic influence and this has in various ways at the different points of his career informed almost everything that he has done. He is also a master of technique on the saxophone; nothing as showy or outwardly revolutionary as John Coltrane; nothing as fast, flashy and out front innovative as Charlie Parker. Yet in its own modest, democratic terms Joe Henderson's playing is every bit as creative and meaningful, the more so because of its humility. Any of the five tracks could be instanced, but listen especially to Joe's soloing on "Totem Pole". Remarkable, defining.

Overall, "The Sidewinder" is an essential album in any jazz collection.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F4%2F2%2F426588.jpg)

/image%2F0964619%2F20240518%2Fob_e065e9_festival-du-livre-1920x1080-4-24-ecran.jpg)

/image%2F0964619%2F20240506%2Fob_4f0709_image-0991366-20181104-ob-95e079-jacqu.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F75%2F17%2F505612%2F129406040.jpeg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F09%2F46%2F497307%2F133747489_o.jpg)